Tuesday 09 November 2010

by: Mike Ludwig, t r u t h o u t | News Analysis

(Image: Jared Rodriguez / t r u t h o u t; Adapted: IRRI Images, Libertinus)

A delegation of politicians and community activists gathered on August 7 in La Leonesa, a small farm town in Argentina, to hear Dr. Andres Carrasco speak about a study linking a popular herbicide to birth defects in Argentina's agricultural areas.

But the presentation never happened. A mob of about 100 people attacked the delegation before they could reach the local school where the talk was to be held.

Dr. Carrasco and a colleague locked themselves in a car as the mob yelled threats and beat on the vehicle for two hours. One delegate was hit in the spine and has since suffered lower-body paralysis. Another person was treated for blows to the head. A former provincial human rights official was hit in the face and knocked unconscious.

Witnesses said the angry crowd had ties to local officials and agribusiness bosses, and police made little effort to stop the violence, according to human rights group Amnesty International.

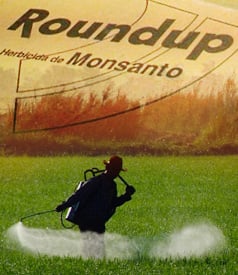

Carrasco is a lead embryologist at the University of Buenos Aires Medical School and the Argentinean national research council. His study, first released in 2009 and published in the United States this past summer, shows that glyphosate-based herbicides like Monsanto's popular Roundup formula caused deformations in chicken embryos that resembled the kind of birth defects being reported in areas like La Leonesa, where big agribusinesses depend on glyphosate to treat genetically engineered crops.

The deformations resulted from much lower doses of herbicide than those commonly found on crops, according to the study.

Biotech chemical giant Monsanto patented glyphosate under the trade name Roundup in the 1970's. The billion-dollar product is a main source of Monsanto's revenue and one of the most widely used herbicides in the world. One Monsanto blogger recently wrote that decades of success has made the Roundup brand name and glyphosate "interchangeable similar to the case of facial tissue and the brand name Kleenex."

Carrasco's report was largely ignored in the mainstream American media, but gained international attention among those opposed to genetically modified (GM) crops like Monstano's Roundup Ready crops, which are genetically engineered to tolerate the glyphosate-based herbicides.

The report is not the first to show that glyphosate herbicides like Roundup are more dangerous than government regulators and Monsanto have claimed, and Carrasco is not the first scientist to face intimidation after challenging the biotech industry, although he is the first to be threatened with violence.

Nevertheless, his report made an impact: journalists covered the results, environmentalists petitioned Argentina's high court to ban glyphosate and the government of the Argentinean province of Chaco began studying an eerie increase in birth defects and child cancer near the soy and rice fields sprayed with thousands of gallons of herbicide.

According to a spring 2010 report released by the Chaco government, an increase in birth defects and child cancer cases coincided with years of agricultural expansion and increased herbicide use in the province. The number of child cancer cases in La Leonesa, the small town where Carrasco and the other concerned citizens were attacked, has tripled from 2000 to 2009 and the number of birth defects in the province nearly quadrupled during that time, according to the report.

The report acknowledges that some local agribusinesses were unlawfully spraying herbicides too close to residential populations, but the Chaco study soon caught the attention of researchers across the world.

In September, an international coalition of scientists released a report citing the attack in La Leonesa and human tragedy in Chaco as proof that Roundup and genetically engineered soy crops are dangerous and unsustainable. The report provides a conclusive rebuttal to the industry's claims that spraying mutant crops with chemicals is the best way to feed the world. It's just another chapter in an information war that has raged for more than a decade, pitting independent scientists and embattled whistleblowers against the world's biggest biotech and petrochemical corporations.

Roundup and Monsanto

Monsanto has gained much of its international notoriety - or infamy, depending on whom you talk to - through its Roundup Ready line of crops that are genetically modified (GM) to be immune to the herbicide. To use the herbicide to combat weeds, farmers must buy patented Monsanto GM seeds with the genetic herbicide tolerant trait. Roundup herbicide is then sprayed to kill unwanted weeds, but the patented GM crops are spared.

The Roundup Ready crop system was first made available in 1996. Since 2000, the percentage of Roundup Ready corn grown in the United States has exploded from 7 to 70 percent and now 93 percent of the soybeans grown in the US are GM, according to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Roundup accounts for about 40 percent of Monsanto's annual revenues and is sprayed on about 12 million acres of American farmland each year. In April, Monsanto announced the completion of a $200 million expansion of its glyphosate production facility in Louisiana.

Monsanto's Roundup Ready patent runs out in 2014, and the Justice Department began an antitrust investigation of Monsanto this year as its petrochemical competitors like DuPont clamor for a piece of the action. Monsanto has proven its tenacity in such disputes in the past; it forged new legal territory in the past decade, suing small farmers who saved Roundup Ready seeds or simply grew crops infected with GM traits after the patented Monsanto gene drifted and multiplied in their fields.

Full story HERE

No comments:

Post a Comment